Twenty years ago, Martin Quezada was told the end was nigh. The sun was setting on the typewriter. Computers were king.

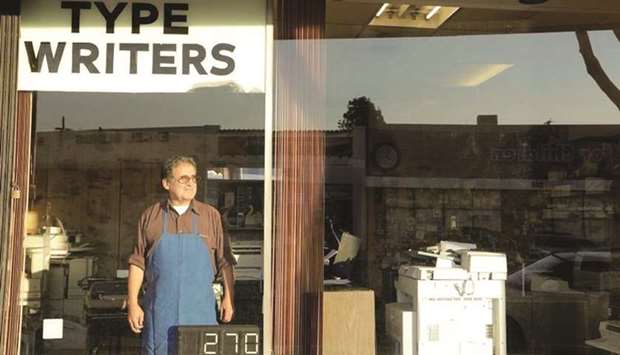

Twenty years later, Quezada’s shop, International Office Machines in San Gabriel, is still in business. The downturn happened. But it did not defeat Quezada, now 61, who kept his doors open.

He had loyal customers — small-business owners set in their ways, retirees unwilling or unable to learn to use a computer. He branched out into copiers and printers. He held on.

Then young people took an interest in antique typewriters.

A group of street poets brought Quezada several to repair. The typewriters were used to write poetry on demand for passers-by.

“At Santa Monica Pier and Seal Beach, those trendy places,” Quezada said.

People ask Quezada to fix old typewriters they purchased on the Internet. He sometimes buys them himself at thrift shops and flea markets. He recently found an Underwood from the 1940s at a yard sale.

In his backroom workshop on a recent afternoon, Quezada pulled handfuls of desiccated ribbon from the 70-year-old machine. He removed the rolling pin-like platen and coaxed tiny springs into place with hooked instruments that resemble dental tools.

If a reporter were not present, he said, he would talk to the typewriter, expressing his frustration with the machine’s finicky innards.

“I will say some things to the machine. I think it helps, when I let him know how I feel.”

But Quezada’s admiration for the machine is clear. The Underwood and its kind “are like Mercedes, like Rolls-Royces,” he said.

They belong to an era before planned obsolescence, when people did not just replace, but repaired, what they owned.

Unlike the pager, the PDA, the floppy disk and the VCR, the typewriter has escaped the heap of gadgets defunct and disused. The reason, according to Steve Soboroff, president of the Los Angeles Police Commission and typewriter collector: Its slow pace is meditative, not frustrating, an exercise in deliberateness closer to engraving than typing on a computer.

“In a world that’s too fast and too easy, a typewriter slows you down,” he said. “If you type a word wrong, it’s wrong. If you miss a space, you missed it. That’s endearing to people now.”

And a typewritten letter is no arrangement of light on a computer screen but a thing, Soboroff explained, a physical expression of thought and care and courtesy. It tells its recipient: You are worth the time it took to type this.

If Soboroff is soliciting donations for a charitable cause, he will type the overture with one of his typewriters. Maybe the 1932 Royal Model P once owned by Ernest Hemingway, or the 1936 Corona Junior used by Tennessee Williams.

“If I send a typewritten letter, I get a 70 percent return rate. If I send it on a computer, it’s about 3 percent,” he said. “It’s unbelievable. If I want a response, I’ll type the letter.”

The typewriter, that is to say, is no charmless, soulless device. In Hollywood, it has famously transcended being a thing to become almost a character: In movies from The Shining — All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy — and All the President’s Men to Schindler’s List. In the adaption of Stephen King’s novel Misery, the typewriter is literally a tool of salvation, used to kill the villain.

Richard Polt, a philosophy professor at Xavier University and self-professed owner of 300 typewriters, said the machines’ performative use has helped spur a renaissance.

“Street typists,” like Quezada’s poetic clientele, became popular in New Orleans and have spread throughout the United States, Polt said. “Type-ins,” or gatherings of typewriter owners at coffee shops and pubs, are “a lot of fun,” he added, as are letter-writing parties.

“There’s this irrational, immediate love of the thing,” Polt said of the typewriter, “like a musical instrument that invites you to create an infinity of things.”

Refurbished, oiled and polished, Quezada estimates the Underwood could sell for $600.

Interest may have been rekindled in the typewriter. But it is not enough to offset what Quezada lost when they tumbled out of use in the late 1990s. Catering to curiosity is no substitute for the contracts with businesses and school districts that sustained his shop for decades.

When Quezada left his Mexican home state of Chihuahua in 1987 to join his sister in San Gabriel, the shop she owned with her husband — an Italian immigrant who repaired typewriters as a boy in Salerno — had servicing contracts with school districts in San Gabriel, El Monte, Whittier and Alhambra.

In the summer, when students were gone and the schools wanted classrooms full of typewriters repaired, the shop had so much business it had to hire temporary workers, Quezada said.

“Around 1980, every little town had a shop that repaired and sold typewriters. A typewriter was expected to be serviced and repaired, and it was expected to last 20, 30 years.”

Quezada took over the shop in the mid-’90s. It wasn’t long before computers were supplanting the typewriter. Though he’s held on, business gets leaner every year, the new interest notwithstanding.

But what else can he do? Besides, he feels there is an importance to his work, beyond providing him a livelihood. Those who come to his shop, to buy a typewriter or have one fixed, need his help to communicate.

“Like the poets, they want to communicate how they feel. It’s important,” he said. “Or older people who cannot write anymore. I have older customers — they say they have to write something, and they cannot hold a pen and cannot use a computer.”

He carries the old Underwood outside, satisfied that its innards are clicking. The sun is setting. He sprays the typewriter down with WD-40 and scours it with a toothbrush. Beneath the blackened bristles, in the fading light, it begins to gleam. —Los Angeles Times/TNS

HOLDING FORT: Martin Quezada Quezada took over the shop in the mid-1990s. It wasn’t long before computers were supplanting the typewriter. Though he’s held on, business gets leaner every year, the new interest notwithstanding.