Imagine The Godfather made by dazzling Latin American directors who combine bravura filmmaking with political awareness and a probing social conscience.

Better than imagining it, see it for yourself in the visually stunning, dramatically gripping Birds of Passage, a film of great scope and passion that was the talk of the Cannes Film Festival when it debuted there last year.

A rare example of provocative cinema on an epic scale, combining genre elements with classic tragedy and cultural fidelity, Birds is the latest film from the Colombian team of Cristina Gallego and Ciro Guerra.

Co-directing here, Gallego and Guerra last collaborated (she produced, he directed) on the extraordinary Embrace of the Serpent, the first film from their country to get a foreign-language Oscar nomination.

Well aware of the sensationalistic drug-trade movies that have come before, invariably done from an American point of view, the filmmakers set out to do things differently, to look at the situation from a Colombian perspective, using compelling technique to keep the dramatic interest at a fever pitch.

Birds also has the advantage of not being told from a generic nationalist viewpoint but from the perspective of the Wayuu people, a powerful indigenous group from the Guajira region in northwest Colombia with a very particular culture.

Though there is a bit of Spanish and a few words of English, almost all of the film’s dialogue is in the Wayuu language (which actress Natalia Reyes learned so perfectly that her native co-stars thought she was one of them).

More than that, Birds is broken up into chapters and framed folklorically, with the story sung by a blind shepherd (think Homer and The Iliad) who introduces us to a tale of “love and desolation, wealth and pain,” a saga of “how a great family destroyed itself.” A happily ever after story this film definitely is not.

Written by Maria Camila Arias and Jacques Toulemonde and inspired by events that took place between the 1960s and the 1980s, Birds does not stint on betrayals, double-crosses and even massacres (thankfully shown off screen).

But it is equally interested in delineating the complex specifics of Wayuu culture and exploring how and why drugs and drug money came into it and the chaos that resulted.

The Wayuu, who co-operated with the filming, live in a particular world where dreams and reality intersect.

(If that sounds a little like the work of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, it turns out that his maternal family were Wayuu, and Wayuu women helped raise him.)

Suspicious of all outsiders, who are called alijunas or “the ones who damage,” the Wayuu are represented by Ursula, played with righteous hauteur by Carmina Martinez, a veteran actress who was born in the Guajiro region and has tribal connections.

A woman of great authority and influence among the Wayuu and someone who believes passionately in the power of family, Ursula is introduced indoctrinating her daughter Zaida (Reyes) in what matters in this life.

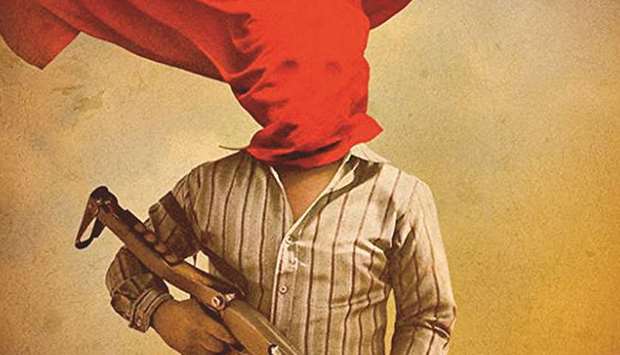

Almost immediately, Zaida, covered in a bright red robe that makes her resemble an enormous predatory bird, participates in la yonna, a stunning courtship dance that showcases how strong the film is in both vivid cinematography (by David Gallego who also shot Embrace of the Serpent) and a site-specific score (Leonardo Heiblum) rich with unsettling echoes of indigenous music.

Dancing with Zaida is Rapayet (Jose Acosta), an ambitious young Wayuu who was raised among alijunas and needs the help of his respected uncle Peregrino (Jose Vicente Cote) to navigate the tribe’s elaborate courtship rituals.

Though he’s a deadly serious young man (Acosta, normally a comedian, affects a remarkable transformation), Rapayet faces a formidable antagonist in Ursula, who insists on a hefty dowry for her daughter’s hand.

Used to doing small business deals with his alijuna partner, happy-go-lucky party animal Moises (Jhon Narvaez), Rapayet catches a break when he hears that some young Americans in the area as part of the Peace Corps are in the market for drugs. It just so happens that Rapayet’s uncle Anibal (Juan Bautista Martinez) is a grower deep in the mountains, and though he is suspicious of alijunas as customers, a deal is struck soon enough.

As the domestic American market opens up and huge sums of money change hands – so much that the bills are weighed rather than counted – it all seems easy enough. Rapayet and Zaida marry and prosper.

But, as Ursula prophetically says, “what’s hard is not making a family, it’s keeping it together.”

Birds of Passage tells a story of a traditional culture fighting for its life against incursions from the outside world, of how insidiously clan ways and spiritual values can be compromised, and it certainly has familiar elements.

But the electric filmmaking, sense of tragedy and cultural specificity are far from usual.

“This was an opportunity to use elements of genre to subvert them” co-director Guerra summed up at the film’s Cannes premiere. “These films are usually glorifications of murders, they never reflect on the damage done to society.”

Or do so in such a memorable, unforgettable way. – Los Angeles Times/TNS

Photo