Critics often claim that China is using its massive “Belt and Road Initiative” as a form of coercive “debt-trap diplomacy” to exert control over the countries that join its transnational infrastructure investment scheme. This risk, as Deborah Brautigam of John Hopkins University recently noted, is often exaggerated by the media. In fact, the BRI may hold a different kind of risk – for China itself.

At the recent BRI summit in Beijing, Chinese President Xi Jinping seemed to acknowledge the “debt-trap” criticism. In his address, Xi said that “building high-quality, sustainable, risk-resistant, reasonably priced, and inclusive infrastructure will help countries to utilise fully their resource endowments.”

This is an encouraging signal, as it shows that China has become more aware of the debt implications of BRI. A study by the Center for Global Development concluded that eight of the 63 countries participating in the BRI are at risk of “debt distress.”

But as John Maynard Keynes memorably put it, “If you owe your bank a hundred pounds, you have a problem. But if you owe your bank a million pounds, it has.” In the context of the BRI, China may turn out to be the banker who is owed a million pounds.

In particular, China may fall victim to the “obsolescing bargain model,” which states that a foreign investor loses bargaining power as it invests more in a host country. Infrastructure projects like those under the BRI are a classic example, because they are bulky, bolted to the ground, and have zero economic value if left incomplete.

Unsurprisingly, some BRI partner countries are now demanding to renegotiate terms, and typically after the projects have started. China may be forced to offer ever more favourable concessions in order to keep the projects on track. In mid-April, for example, Malaysia announced that a major BRI rail project, put on hold by the government after last year’s election, would now go ahead “after renegotiation.” According to media reports, the costs of construction were reduced by as much as one-third. Other BRI countries will probably also ask for debt forgiveness and write-offs, the costs of which will ultimately be borne by Chinese savers.

The BRI may well have additional hidden costs for China down the road. For starters, it is extraordinarily difficult to make money on infrastructure projects. There is a widespread belief that infrastructure investment powers economic growth, but the evidence for this is weak. In fact, China itself built much of its current infrastructure after its growth had taken off. In the 1980s and 1990s, for example, China grew much faster than India despite having a shorter railway network. According to the World Bank, in 1996 China had 56,678km (35,218 miles) of rail lines, and India had 62,915km. Chinese growth was not jump-started by infrastructure, but by reforms and human capital investments. If growth fails to materialise in BRI countries, Chinese companies may end up bearing the costs.

Furthermore, many of China’s BRI partner countries are risky – including Pakistan, a major recipient of investments under the scheme. In addition to its high political, economic, and default risks, the country also scores poorly on education indicators. According to one report, Pakistan ranked 180th among 221 countries in literacy. This is a potential red flag for Chinese investments in Pakistan, because research suggests that investments in physical infrastructure promote growth only in countries with high levels of human capital. China itself benefited from its infrastructural investments because it had also invested heavily in education.

Nor should the BRI be compared to the Marshall Plan, the US aid programme to help rebuild Western Europe after World War II, as an example of how large-scale investment projects can boost growth. The Marshall Plan was so successful – and at a fraction of the BRI’s cost – because it helped generally well-governed countries that had been temporarily disrupted by war. Aid acted as a stimulus that triggered growth. Several of the BRI countries, by contrast, are plagued by economic and governance problems and lack basic requirements for growth. Simply building up their infrastructure will not be enough.

Finally, the BRI will probably further strengthen China’s state sector, thereby increasing one of the long-term threats to its economy. According to a study by the American Enterprise Institute, private firms accounted for only 28% of BRI investments in the first half of 2018 (the latest data available), down by 12 percentage points from the same period of 2017.

The BRI’s massive scale, coupled with the lack of profitability of China’s state sector, means that projects under the scheme may need substantial support from Chinese banks. BRI investments would then inevitably compete for funds – and increasingly precious foreign-exchange resources – with China’s domestic private sector, which is already facing a high tax burden and the strains of the trade war with the US.

Moreover, Western firms, an important component of China’s private sector, are retreating from the country. Several US companies, including Amazon, Oracle, Seagate, and Uber – as well as South Korea’s Samsung and SK Hynix, and Toshiba, Mitsubishi, and Sony from Japan – have either scaled down their China operations or decided to leave altogether. Partly as a result, US foreign direct investment in China in 2017 was $2.6bn, compared to $5.4bn in 2002.

This is a worrisome development. Through the BRI, China is building ties to some of the world’s most authoritarian, financially opaque, and economically backward countries. At the same time, a trade war, an ever-stronger state sector, and protectionism are distancing China from the West.

China has grown and developed the capacity to undertake BRI projects precisely because it opened its economy to globalisation, and to Western technology and knowhow. Compared to its engagements with the West, the BRI may entail risks and uncertainties that could become problematic for the Chinese economy. As the Chinese economy slows down, and its export prospects are increasingly clouded by geopolitical factors, it is worth rethinking the pace, scope, and scale of the BRI. – Project Syndicate

* Yasheng Huang is International Program Professor in Chinese Economy and Business and Professor of Global Economics and Management at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

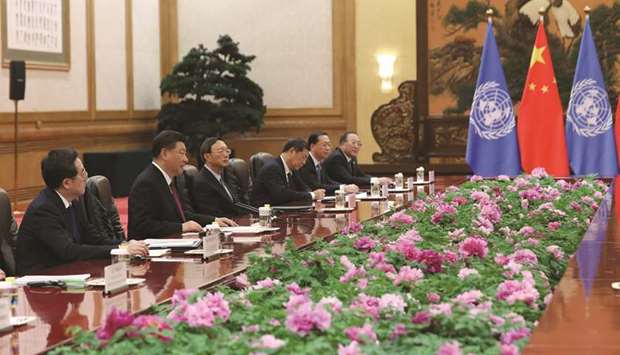

File photo: Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks during the bilateral meeting of the Second Belt and Road Forum at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing last month.