“Go.”

The drive from the songwriter’s hotel to a dinner being held in his honour will take no more than 30 minutes, and he does not want to waste any of them. He likes to be in control. Some of the first words he utters in a new documentary about his life are a warning to its director: “You think that you’re just going to put this film together and it’s going to be exactly the way you want it. But it’s not, because I’m going to be over your shoulder the whole … way.”

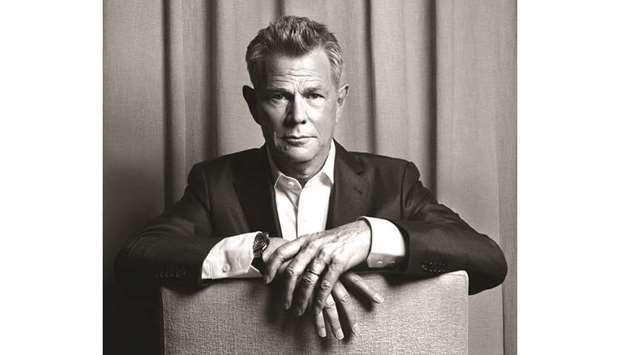

“Could I have been more wrong? I had zero control,” he says now, as the car idles in traffic in downtown Toronto, where David Foster: Off the Record premiered last week at the local film festival.

The notion that Foster, 69, did not have final cut on the film is kind of unbelievable, given how positively glowing it is about his life. In interviews with some of the dozens of musicians he has worked with throughout his career — Barbra Streisand, Celine Dion, Josh Groban, Lionel Richie — we hear about what a musical genius he is. Billboard called it a “90-minute testimonial exulting his excellence,” an “infomercial” permeated with Foster’s “arrogance and self-congratulatory attitude.”

Is he cocky? Sure, he’ll admit that. “But can you really do all that I’ve done and not be confident?” he asks. “When you see your peers and they’re not doing what you’re doing, you know you must be good.”

Foster does, in fact, have plenty to boast about. He’s won 16 Grammys. He wrote hits like Whitney Houston’s I Have Nothing and Chicago’s Hard to Say I’m Sorry and produced ones like Donna Summer’s Last Dance and Toni Braxton’s Un-Break My Heart. He also single-handedly discovered Dion, Groban and Michael Buble, turning them into global superstars.

In theory, he is a fascinating documentary subject. Beyond his storied music career, he has led an eccentric personal life. In June, he wed the singer and actress Katharine McPhee, who is 34 years his junior. It’s his fifth marriage, following other famous partnerships with Linda Thompson — ex-wife of Caitlyn Jenner, with whom she had sons Brody and Brandon — and Yolanda Hadid — mother of the models Gigi and Bella.

While he was married to Thompson, he had his first foray into reality television: The Princes of Malibu, a 2005 Fox show that presented him as a grump fed up with the antics of his stepsons and their best friend, future The Hills villain Spencer Pratt. Then, in 2012, he turned up on Bravo’s The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills alongside Hadid. Foster often appeared on the show, presiding over the $19-million Carbon Canyon seaside mansion where he invited the housewives to intimate cocktail parties at which Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds performed. The pair’s 2015 divorce was also chronicled on the programme, a split that Hadid blamed on her chronic Lyme disease.

“I’m starting to feel that David is unhappy with the fact that I can’t be by his side the way that I used to be,” she wrote in her 2017 memoir. “I feel as if he’s starting to get impatient with my recovery.”

‘Wish I hadn’t’

In the new documentary, Foster says their breakup had nothing to do with Lyme disease but declines to elaborate further. He does not think fondly of his time on Housewives and is upset that he is often recognised on the street as a reality TV star instead of a music legend.

“The Beverly Hills Housewives was just kind of a nightmare for me and something that I really wish I hadn’t been part of,” he says, adjusting his suit jacket. He begins to recount a story about how, while watching his son-in-law play in a professional tennis tournament in San Jose, he was approached by a television reporter who asked if he’d do an interview with her.

“First question: ‘So, what’s Lisa Vanderpump really like?’ It was all about the Housewives. I wanted to say, ‘I’ve got 16 Grammys, b---h!’ But I didn’t. … A lot of people loved that show. I can’t imagine why, but they did.”

Despite his negative experience with reality television cameras, he says he was not reluctant to open his life to a documentary crew. The film, directed by Barry Avrich, came about as a collaboration between Canada’s Walk of Fame and Bell Media.

“They had this idea that maybe past recipients of the Walk of Fame should have documentaries made about them, and I came up as the first subject,” recalls Foster, who was raised in Victoria, British Columbia. He spent about a year and a half working with the filmmaker, allowing Avrich to trail him on a trip to New York City, where he is trying to get a Broadway musical mounted. Broadway is the “mountain I still want to climb,” Foster explains. He has four theatre projects in the works but acknowledges he has trouble with the process, which requires numerous collaborators.

“But I’m not a quitter. It just feels like a logical next step for me,” he says. “In my career, I’ve always used the phrase ‘retreat and attack in another direction.’ At the end of the ‘90s, all of a sudden I found myself the guy that couldn’t write a Top-40 hit record after 25 years of writing hits. The paradigm shifted. N’Sync and the Backstreet Boys came in and I didn’t really know how to deal with that Swedish sound. So I was like, ‘I don’t know how to do that, but maybe I’ll go over here and get myself a little Josh Groban and a little Andrea Bocelli and a little Michael Buble and we’ll sell just as many records, if not more, than everybody else — we just don’t need Top 40 to do it. Television [talk shows] will become our radio.’”

Foster is keenly aware that pop music has moved from the power ballads that made him famous. “Kids don’t have an appetite for it,” he says with a shrug. It’s not that he hates today’s music. He’s a big fan of Ariana Grande and Ed Sheeran. He just knows where he belongs, and it’s no longer in Top 40 music.

“It’s just a matter of age. Times move on, sounds move on,” he says. “I think there’s a little part of me that would love to get together with, like, Ariana’s guy, Tommy [Brown], and the Drake camp and all these young writers that are so great. There’s a part of me that would like to spend a year dancing around their studios.”

In 2015, he joined Grande on stage at the Forum, playing piano as she belted a version of Houston’s I Have Nothing. He loved the experience, he says, except for the fact that the audience was disappointed when the singer brought him on stage instead of co-headliner Justin Bieber. And yet for the last few years, he’s really only worked with Buble. It’s not that he’s interested in retiring. But he’s anxious at the thought of being able to replicate the success of his glory days.

“Maybe what’s stopping me is the potential of failure,” he says. “And also, quite honestly, a lot of those guys, they have a style that is hard for me to wrap my head around. The songs get passed from room to room, and there are seven or eight writers on them. That’s not really my style.”

Music and marriage

McPhee would inspire him to go back into the studio. But because the American Idol runner-up has spent so much of the last few years acting — first on NBC’s Smash, most recently in Broadway’s Waitress — she’s “not motivated as a singer,” Foster says.

The 35-year-old was a part of the documentary, though by her own admission she was reluctant to participate because it was “David’s thing.” In one shot, the couple sit by a piano in their home and acknowledge the “unorthodox” nature of their relationship.

“But in a relationship, there’s 10 things that can bring you down or pull you apart and break you up,” Foster says as his car nears its destination. “You don’t sleep well together, the in-laws are terrible or whatever. Having an age gap — which we have a significant one — is just one of the 10. If we don’t have the other nine — if that’s our only obstacle — we’re gonna make it.”

Foster’s black SUV has arrived at the Four Seasons, where, upstairs, Avrich is throwing a private dinner for the musician. McPhee is waiting in the ballroom, as are some of Foster’s five biological children. The one part of the film that was uncomfortable for him to watch, Foster admits, was the section in which his kids talked about his parenting. Many described how difficult it was to have him spend so much time working — and to see him serve as the stepparent to new children every time he remarried.

“And forget everything else, being the child of a successful person is probably difficult, which is something I’ve never given a thought to,” he says. He notes that his offspring are all “doing great” now: Two of his daughters, Sara and Erin, just landed a TV deal at 20th Century Fox, and another, Amy, has written all of Buble’s hit songs.

“My kids, they don’t have trust funds,” he says. “They don’t have millions of dollars in the bank. Well, if they do, it’s not because of me. I’ve given them just enough help, and I feel good about that.”

He gets out of the car and searches for a hotel representative, who points out where the entrance to the staircase is. Dinner is on the sixth floor, but Foster will be walking. “You know I don’t take elevators, right?” he says. “I’m claustrophobic. Fosterphobic.” — Los Angeles Times/TNS