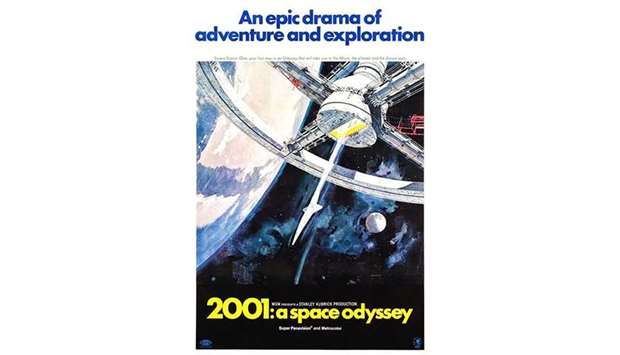

Though the calendar reads 2020 we’re still waiting for the future promised in 2001. Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film, created concurrently with Arthur C Clarke’s novel, is recognised as one of the most influential motion pictures ever made, endlessly scrutinised from both a story and production point of view. Both avenues are open to New Yorkers and visiting tourists from tomorrow through 19 July at the Museum of the Moving Image adjacent to the Kaufman Astoria Studios in Queens.

Envisioning 2001: Stanley Kubrick’s Space Odyssey is an in-depth examination of how the New York-born director’s desire to make “the proverbial ‘really good’ science fiction film” (as Kubrick wrote to Clarke in a letter preserved under glass in the exhibit) led to “the ultimate trip”, as MGM’s marketing department called the movie once young people seized upon the heady, ambiguous film that exploded into sound and light to go “beyond the infinite” in its most notable sequence.

That section of the movie — the stargate scene — is what greets you as you climb the stairs to the museum’s third floor. There are also smaller screens offering clips from films that directly influenced Kubrick when he was dreaming of the future. To the Moon and Beyond, created for the 1964 World’s Fair, sits beside the George Pal-produced Destination Moon. Jordan Belson’s experimental shorts and the Soviet-influenced Czech masterpiece Ikarie-XB1 flank the National Film Board of Canada’s 1960 short Universe, narrated by future voice of HAL 9000, Douglas Rain.

During the press preview, Kubrick’s eldest daughter, Katharina, said “teenage boys made that movie a success”, as she detailed the initial critical drubbing her father’s vision of tomorrow faced on release, and how counting the walkouts with a clicker during the premiere left the director “feeling depressed”. When she heard a radio DJ call it “groovy”, she knew it might catch on.

“Today,” she continued, “young people are very enthusiastic about the film. It’s Goat [greatest of all time], or whatever it is,” she joked, mentioning its frequent revivals and the recent Christopher Nolan-led “unrestored” release.

Her father’s exhaustive research is made wonderfully evident in the exhibit with large amounts of correspondence on show, awaiting a deep dive. No detail in the finished film wasn’t thoroughly discussed between the production team and groups like the Rand Corporation or Ordway Research. One can also inspect the deals with groups like Hilton Hotels or Parker Pens because even an arthouse masterpiece from the 1960s made room for spon-con.

The model ships, drawings, sketches, costume tests, helmets, props, walls of index cards and apeman suits are what one expects from an exhibit like this, but what grabbed me most was a special section dedicated to the stargate sequence. I’ve read about Douglas Trumbull’s creative use of the split-scan technique (which the twentysomething tinkerer essentially invented on the fly) but I’ve never quite understood it before. Seeing the enormous schematics and large-format photos finally brought that home.

Not that I’d ever let go of the suspension of disbelief. With the eerie György Ligeti music piped in (and, elsewhere, Aram Khachaturian and Strausses both Richard and Johann) one is quickly reminded that all this behind-the-scenes magic wouldn’t mean much without the ideas Kubrick and Clarke dreamed up.

“It doesn’t tell you what to think,” Katharina Kubrick says of the film, the first of her father’s works she was old enough to see on its release. (“I certainly wasn’t allowed to see Lolita,” she joked.) “Who you are is how you receive it,” she continued, adding that her father remained a “proud Bronx boy” who would receive VHS tapes of New York football and baseball games from his sister when the family lived in England.

The film’s New York roots are a point of pride for the museum. Kubrick and Clarke’s first meeting was held at the long-gone midtown bar Trader Vic’s. Clarke, already living in Colombo in modern-day Sri Lanka, was in town to work on Time-Life Library’s Man and Space. The pair talked through the story in Kubrick’s frenetic apartment with three energetic young daughters on Lexington Avenue, his office on Central Park West and on walks between the two. When physical production moved to Borehamwood in Hertfordshire, Clarke stayed on at Manhattan’s Chelsea Hotel to work on the novel.

2001: A Space Odyssey was the first film the Museum of Moving Image programmed after its rather Kubrickian remodelling job in 2011. (The architect Thomas Leeser admitted to the movie’s influence, according to opening remarks at the press event.) The film has screened 46 times to packed houses at the museum since 2011, one of the few spots left in New York with exquisite 70mm projection.

The new exhibit comes to New York after a successful run at the Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum in Frankfurt. It represents all of the 2001 elements (with “amplification”) from a larger Stanley Kubrick show that toured London, Los Angeles and numerous other cities.

With six months of Envisioning 2001 in the upstairs gallery, many special guests like Douglas Trumbull, 2001 actors Keir Dullea and Dan Richter and the director of the Carl Sagan Institute, Lisa Kaltenegger, are booked for accompanying film screenings. In addition to 2001 on both 70mm and digital, programmes include films that inspired Kubrick, were influenced by 2001 or are notable “outer space speculators”. From now until July, Queens, New York is the ultimate trip. — The Guardian

..