In the broad sweep of American history, certain years stand like grim mileposts. The year 1968, bathed in blood and drenched in sorrow, is one. The year 2020 may be another.

The US is convulsed today in a way it has not been in more than half a century: stalked by a mysterious virus, burdened by soaring joblessness, wrestling — once again — with the twin plagues of racism and inequality that have poisoned the country from its outset.

As it happens, 1968 was a presidential election year. So, too, is 2020. It is the time when Americans take stock of what has been and look forward, with varying degrees of hope and resignation, to what may be.

So much has changed in 52 years. So much remains the same.

Every election amounts to a choice, between candidates but also between possibilities. Given these unnerving times, the vote on November 3 could very well matter more than any election in a generation.

That’s what happened the last time the country cast its ballots for president amid such an air of foreboding.

In 1968, the country was torn apart by an ill-conceived war fought in the cities and jungles of far-off Vietnam. Americans came to realise the conflict was a lost cause and, worse, grew to understand their leaders had lied to cover up their own doubts about the war and ineptitude prosecuting it.

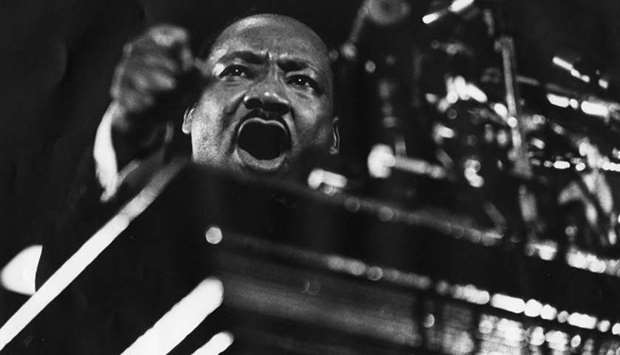

The Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., the nation’s leading apostle of nonviolent protest, was shot and killed at age 39 for dedicating himself to the proposition that all men, no matter the colour of their skin, were created equal. Scores died as more than 100 cities around the country went up in flames.

Robert F Kennedy, age 42, was shot and killed two months later after inveighing against the Vietnam War and taking up King’s torch.

In Chicago, rogue police smashed the heads of demonstrators at the Democratic National Convention after carefully removing their badges to avoid identification. Inside the hall, reporters were roughed up. When Connecticut Senator Abraham Ribicoff objected to the police tactics, his speech was greeted with a stream of profanity and anti-Semitic invective from the city’s mayor, Richard J Daley.

“It felt like the foundations of the country were trembling, which in fact they were,” said Allen Matusow, a fellow at the Baker Institute of Public Policy at Rice University, who has written extensively about the 1960s.

Today, our ground seems similarly shaky.

“We’re not stable in terms of our health,” said Peter D Hart, who marked 1968 by quitting his career as a nonpartisan polling analyst to become a Democratic campaign strategist. “We’re not stable in terms of our society and we’re not stable in terms of our economy.”

In November 1968, Republican Richard Nixon won the White House after promising to quell the country’s unrest and restore “law and order” to its sundered streets. The popular vote was close — Nixon just slipped past Democrat Hubert Humphrey — but the outcome wasn’t really. Nixon crushed Humphrey in the Electoral College and probably would have won by a greater margin if Alabama’s segregationist governor, George Wallace, hadn’t carried five Southern states.

It’s been said that history doesn’t repeat itself but it does rhyme, which suggests a set of recurring patterns. Indeed, there are through lines from 1968 to today.

One of Nixon’s campaign strategists, Roger Ailes, helped found Fox News and its high-octane formula of pugnacious conservatism. Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign echoed Wallace’s bombastic populism and the governor’s thinly veiled appeals to racial prejudice and bigotry; lately, as Trump seeks re-election, he has begun to echo Nixon, calling himself “your president of law and order” and speaking of a “silent majority” cowed into quiescence.

Those old enough to remember may be experiencing 1960s flashbacks (of a no pharmaceutical sort) for good reason. As historian Rick Pearlstein noted, “The soft domestic civil war of the 1960s created the order of battle of our political discussion today.”

The conflict between conservatives and liberals, or progressive as some prefer, is familiar enough. So, too, is the raging culture war, even if the terms of engagement have changed; we no longer fight over long hair and blue jeans but rather protective masks and hydroxychloroquine.

And yet this is not 1968.

America is a vastly different, if still troubled, place.

It was only in 1967, in the felicitously named Loving v Virginia, that the Supreme Court upheld the right of black and white Americans to marry. Today, that right has been extended to same-sex couples.

Whites are a shrinking portion of the population and, significantly, the electorate. There may still be cavernous differences in incomes and equality, but seeing black and brown faces in corporate boardrooms or seated at negotiating tables in Congress and statehouses around the country no longer prompts wonderment.

Today’s protests are smaller in scale and, thankfully so far, much less deadly. Strikingly, they are also vastly more integrated and greeted with much greater support and sympathy. In some instances, police officers have laid down their batons and marched with demonstrators, or dipped to one knee to show their solidarity.

The horrific death of George Floyd under the weight of a white policeman has been universally condemned, even by the agitprop commentators on Fox News. Compare that with attitudes at the time of King’s assassination, which occasioned the Chicago Tribune to editorialise against the perceived rending of the country’s social fabric.

“If you are white, feel guilty about it,” the editorial stated. “Yield the sidewalk to the migrants from the south that has descended on your cities. Honour their every want, because the ‘liberals’ tell you that it is your fault that they have not educated themselves, developed responsibility, trained themselves to hold jobs, or are shiftless and dependent on your taxes.”

The sentiment was hardly outside the norm.

California Governor Ronald Reagan, who waged a brief unsuccessful 1968 challenge to Nixon for the GOP nomination, was among those who suggested King and his civil disobedience helped sow the seeds of his demise, calling the event “a great tragedy that began when we began compromising with law and order, and people started choosing which laws they’d break.”

And yet here we are, again.

This coronavirus may be novel, but not the disproportionate effect it has had on black Americans, who are more likely to lose their jobs or get sick and die.

Once more the cities, and its affluent suburbs, are the scene of protest and looting because once again another black man has been killed by a white police officer meting out his twisted version of justice. Once more there are incidents of law enforcement officers, some with their badges covered or removed, indiscriminately cracking down on peaceful demonstrators.

There is something particularly resonant and insidious in the fact the latest spark was struck not in the Deep South, with its benighted racial history, but in Minnesota, where Humphrey emerged as an early and forceful advocate of civil rights and liberals cherish the legacies of Walter Mondale and Paul Wellstone.

America’s road toward that more perfect union is long and tortured, and anything but a straight line from injustice to remediation. And yet it moves forward.

Alan Shane Dillingham, 38, is an assistant professor of history at Spring Hill College in Mobile, Alabama, and one of a new generation taking a fresh look at the legacy of the 1960s. “This isn’t just chaos,” he said of the upheaval arising from Floyd’s killing. “Certainly it’s concerning. But oftentimes in American history riot and rebellion have produced tangible changes to American society.”

Already, political lines are drawn.

Trump has hardened in his resolve to crack down on demonstrators, threatening to deploy the military if necessary. His Democratic rival, Joe Biden, has called for reforms, promising to create a police oversight board within his first 100 days in office and calling on Congress to immediately pass legislation outlawing the police use of chokeholds. There is virtually no overlap.

Rare is the election held in times as fraught as these. Rarer still is an election as significant as 1968 was and 2020 may prove to be.

— Los Angeles Times/TNS

BLAST FROM THE PAST: Martin Luther King speaking at Vermont Avenue Baptist Church in Washington in 1968.