By Steve Rose

“You get used to sticking a six-inch cotton-wool bud up your nose and down your tonsils every morning,” says Richard Clark. He is describing his typical working day. “The masks are quite suffocating. They’re quite sweaty. You don’t drink as much water, and so people dehydrate. You get headaches. Certainly on the first week, by five o’clock, a certain kind of fugginess comes over everybody. Concentrating during those last two hours … you can feel it being a little bit harder.”

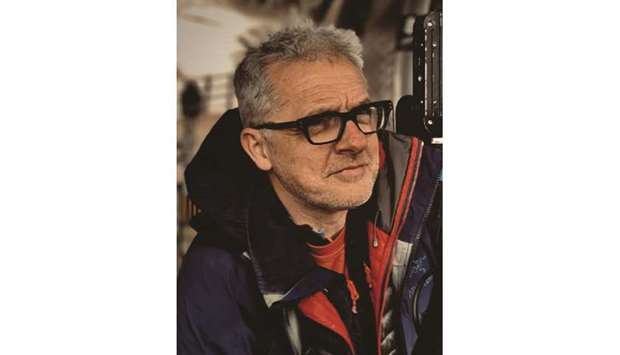

It sounds like the experience of a frontline care worker, but this is film-making in the age of Covid-19. Clark is directing the second season of Fox’s apocalyptic sci-fi series War of the Worlds in south Wales, with a crew of about 70 people. Having shut down in late March because of the pandemic, the UK’s film and high-end television industry is back in business, which can only be good news. But it is by no means business as usual. As the director of one of the first productions to resume, three weeks ago, Clark has been negotiating a whole new way of working — not quite as dystopian as the programme he’s making, but strange and slightly sci-fi all the same

“To be honest, you get used to the patterns and the rituals pretty quickly,” he says. “Testing is the key thing: temperature checks for everybody every morning, and 30 members of the crew and the lead actors are tested every morning.” There is a full-time Covid-19 consultant on set to keep an eye on social distancing and cross-contacts. Sets are fogged every night, as are all the costumes. Props are kept sealed in bags, then only handled by the cast member using them. Even dining is different, with no more catering truck and lunchtime socialising. Meals are individually packaged and served, and eaten in a huge marquee. Each table is two metres long, so one person can sit at either end.

“The main philosophy behind how we operate is essentially: ‘You’ve got to protect the cast,’” Clark explains. In War of the Worlds’ case, that includes Gabriel Byrne, Elizabeth McGovern and Normal People’s Daisy Edgar-Jones. “Ultimately, the crew are replaceable, including — to an extent — the director. But the lead cast are not, so you’ve got to prioritise safeguarding those personnel who, if they went down ill, would cause the whole thing to collapse.” There is a complex system of coloured armbands denoting the degree of proximity to which crew members are allowed to the actors. Everyone must wear masks, even when shooting outdoors. Some, such as hair and makeup, must wear visors, too.

It is a similar setup over at Pinewood studios, says Sarah-Jane Wright, the head of production at Working Title. She has just returned from the set of Last Night in Soho, Edgar Wright’s new movie, a psychological horror set in 1960s London. Shooting was just about finished when lockdown started, but a week of additional photography was still needed. With a larger crew, their system is even more complicated than Clark’s. Personnel are divided into discrete pods. Pod A is the cast (which includes Anya Taylor-Joy, Diana Rigg and Thomasin McKenzie) along with crew who have to be close to them, such as the director and camera operators. They have their own separate entrance and check-in area (again, temperature checks and Covid-19 swab tests are routine), separate bathrooms and their own dining facilities. Pod A can only interact with their “pod unit base”, which consists of hair and makeup, second assistant directors and others.

Pod B contains other technicians and crew who have to be on set. They are separated from pod A by Plexiglass and barriers. Pod C is standbys, electricians, grips, riggers and props, who have their own marquee outside the set. “If a light needs changing or props need adjusting, they can only go on to the set when pod A and pod B have cleared it.” Then there’s Pod O (office and props, who are nearby but never come on set), and Pod H (people working remotely). Plus 24-hour cleaners and a team of between six and 10 Covid-19 co-ordinators, swabbing nurses and medics. “We have a very good Covid adviser who does actually have a metal measuring tape to make sure everyone is two metres socially distanced.” Because everyone is in masks, things are quieter than usual, says Wright. “It can feel as if you’re going to work in an operating theatre. But it has so quickly become our new normal.”

Before coronavirus, film and high-end television production in the UK was booming. Inward investment, mostly from the US, was at a record-breaking £3.65bn in 2019. This year was on track to exceed that. The major film studios were fully booked, new ones were being built across the country to cope with the demand and Hollywood productions were queueing up to take advantage of the UK’s expertise and tax breaks. Then, with the imposition of lockdown in March, everything changed practically overnight. “We went from pretty much full employment to zero employment and everything stopping,” says Adrian Wootton, the CEO of the British Film Commission (BFC), which is responsible for persuading foreign companies to come and film in the UK. “We had something like a billion pounds— worth of production mothballed or suspended in the UK.”

The BFC, British Film Institute and others have been working ever since to figure out how to get film-making back up and running, talking to industry, studios, unions, government, public health bodies, right up to No 10. It was the biggest consultation they have ever done, according to Wootton. The end result was a 53-page document of guidelines for working safely during Covid-19, published in June but continually updated since. It has served to kickstart the recovery process. “Pretty much from the minute the guidance was published, people started rehiring their teams, and started going back into active preproduction,” Wootton says.

That recovery is proceeding apace. At the beginning of July, Tom Cruise arrived in the UK to resume filming on Mission: Impossible 7 and 8 at Hertfordshire’s Leavesden studios (filming in Italy was halted in February). Cruise was one of a number of actors to be granted exemption after standard quarantine rules were relaxed to allow Hollywood crews to work in the UK under socially distanced conditions. Across the Pinewood lot from Last Night in Soho, Jurassic World: Dominion is back on set, having shut down in March. Other titles such as The Batman, Disney’s The Little Mermaid and Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them 3 are preparing to start up again. Netflix expects its UK series such as The Witcher and Sex Education to be filming by the end of September. Bollywood is also returning to the UK: Akshay Kumar’s Bell Bottom is due to shoot in Scotland in August.

Film-making under Covid-19 will be more expensive. Working to the guidelines is adding between 15% and 25% to gross budgets, estimates Sarah-Jane Wright, on top of money lost by shutting down. At the time of lockdown, Working Title had four films scheduled to begin shooting this summer. Universal has spent a reported £5m on safety protocols for Jurassic World at Pinewood. The US studios have deeper financial resources and resilience, but for smaller domestic TV and independent film productions the costs have been prohibitive. Insurance has been a particular barrier to restarting, although that problem was finally resolved this week with a new £500m government-backed support scheme.

Film-making is also expected to be slower under the guidelines, although Wright and Clark report no major schedule delays. “At the moment, we are shooting about 18 setups a day, which is what I aim for in a high-end drama,” says Clark, “so we are not dropping anything.” Much of that is down to the military-level planning required in the preproduction phase. Another factor could be the reduced number of interruptions, now that nonessential personnel cannot casually drop by to “see what’s going on” or surreptitiously gawp at Tom Cruise.

Long-term lessons could yet come out of this situation. As with many sectors, the film industry seems to have realised how much more people could be working remotely. There are also, suggests Wootton, lessons about sustainability – never one of the industry’s strong points. “Big productions such as James Bond move around the world, and you can’t see that changing, but there might be more: ‘Do we really need to go to that country? Do we really need to send hundreds people on a jet there for several weeks?’”

As for the creative impact, the new working conditions make certain scenarios more difficult. Crowd scenes, for example, or street scenes requiring lots of extras, all of whom must be tested, monitored and socially distanced. But there are always workarounds. This week’s shooting on Last Night in Soho was originally supposed to have taken place in the real Soho in central London; instead they have had to recreate the streetscape on a soundstage with visual effects filling in the gaps. Clark has not had to make changes to War of the Worlds’ scripts, he says, but he, too, has had difficulties finding locations, since so many places are shut down or high-risk, which has necessitated building more indoor sets.

One small but significant difference, Clark observes, is how protective equipment and social distancing affect human interaction: “It puts a slight wall between you that wasn’t there before. It’s surmountable, but you feel it. There’s a kind of intimacy in terms of directing, and particularly with the cast. We shot a very emotional scene this morning and it was quite upsetting for the actor, and it was hard maintaining a distance from them. Usually, there would probably be a touch on the arm, a physical reassurance. Actors make themselves very vulnerable, and they need the support and reassurance of directors to help them go there, and know that it’s safe. That reassurance is slightly harder to provide if you’re a metre-plus away from them with a mask on.”

Nobody wants this “new normal” to last, but film crews are well accustomed to coping with adverse and unpredictable conditions, points out Sarah-Jane Wright. “If any industry was going to adapt to this, the film and TV industry is built to just take this on board and run with it. If this is our normal for the next year, I feel we can achieve it. When I visited the set, there was a real sense that everyone was really, really happy to be back at work … although it’s hard, because you can’t see people smiling through a mask.” Clark agrees: “Being in a mask 10 hours a day is not fun, but these are not exactly terrible problems. We’re all bloody grateful to be working, to be honest.” – The Guardian

..