Joe Biden’s promise to bridge the racial economic gap needs buy-in from one powerful person — Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell — and he doesn’t sound convinced.

The Democratic presidential nominee wants the Fed to “aggressively” target inequality, even leaving open the possibility of asking Congress to create a third mandate for the central bank. Biden has vowed to nominate minorities to the Fed’s leadership ranks, and if he wins in November would have at least three opportunities to do so in a first term, including the chair.

Powell has downplayed the idea of a direct role for the Fed in tackling racial inequality, saying in July that its underlying causes “are not related to monetary policy” and that fiscal efforts “and just policy generally: education, health care, all those things” can be more effective remedies.

Such reticence could put him at odds with a President Biden. Powell’s current term as chair expires in February 2022.

In May, Powell said Fed policies “absolutely” don’t add to the nation’s economic inequality. Last month, he said that while wealth disparity is a “critical problem,” central bankers “don’t really have the best tools” to address it.

Powell could, however, use the Fed’s role as a regulator to do more to encourage banks to support minority communities’ access to credit and financing.

“It’s undeniable that the Federal Reserve’s policies have had an effect on the disparities,” said Seth Carpenter, chief economist for UBS LLC who previously worked at the Federal Reserve Board. “When monetary policy is restrictive, unemployment generally rises, but for Blacks it rises more. It’s traditionally been the practice to ignore these differential effects.”

Powell, a Republican appointed to the Fed’s top job by President Donald Trump, has acknowledged that the central bank can run the economy hotter than once thought, helping the benefits of a tighter labor market reach minority communities.

Biden wants the Fed to do more to acknowledge its role in the disparities. He’s floated the idea of asking Congress to amend the Federal Reserve Act to require it to report on racial economic gaps and what policies it is implementing to close those.

The Fed a dual mandate from Congress to promote maximum employment and stable prices. Although he has not explicitly called for a third mandate, Biden hasn’t ruled it out, either.

“This proposal does not call for a third mandate. It calls for a reporting requirement that imposes accountability on the Fed to actually measure progress toward closing racial gaps,” said Jake Sullivan, Biden’s senior policy adviser. “However, he’s not taking off the table that at some point, depending on how that plays out, that one could think about broadening the mandate.”

Democrats including Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Representative Maxine Waters of California are among those who’ve proposed new legislation for the Fed that would require it to shrink inequality. A Fed spokesperson declined to comment on the proposals.

Jared Bernstein, who served as chief economist to Biden when he was vice president and still advises the candidate informally, says progress can be made without a third mandate. Congress can add “racial wealth gaps” to the list of variables that the Fed must provide written reports on to lawmakers, he said, which would open “a floodgate of high-level research into the problem.”

Biden’s economic policy advisers say that the Fed should talk openly about the data that shows wide discrepancies by race.

Black workers have seen higher unemployment rates than other races for decades. So Biden’s camp says it’s wrong to consider a 5% jobless rate as “maximum employment,” as some did at the Fed in 2015, a time when the jobless rate for African-Americans remained at 9.4%.

The central bank during that period was led by Janet Yellen, a Democrat appointed by President Barack Obama, and its first female chair.

“We can’t say we’re done fixing the economy when the jobless rate is at 5%. That’s the wrong message when we have such deep inequalities,” said Heather Boushey, president and CEO of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, and a Biden adviser.

“Focusing on aggregate indicators is not giving policy makers enough texture on how to make policy, and this needs to be acknowledged in the messaging,” said Boushey, who spoke at the Fed about racial inequities earlier this year.

Powell, more than his predecessors, agrees that the Fed has learned the lessons of the last recovery — that unemployment can fall lower than thought without sparking too-high inflation, and that this can spread labor-market gains more widely.

“We want to remind ourselves that prosperity isn’t experienced in all communities,” Powell told Congress in November. “Low- and moderate-income communities in many cases are just starting to feel the benefits of this expansion.” The Black unemployment rate at that time was 5.5%, while for Whites it was 3.2%.

Federal Bank of Chicago President Charles Evans on Sunday said that through the latest crisis, the “inequality gap has persisted” between Whites and minorities. He noted that Black unemployment is currently over 14% while White unemployment is 9%.

The summer’s nationwide protests against racism highlighted that African Americans lag other groups in nearly every economic measure. Biden, who has overwhelming support from older Black voters but needs to inspire younger Black adults to vote for him, has made racial equity a pillar of his four-part, $3.5tn plan to trigger an economic revival.

These issues, in large part, come down to lack of diversity at the Fed, Rhonda Sharpe, head of the Women’s Institute for Science, Equity and Race, or Wiser. “We need a set of folks who have diverse life experiences,” she said.

The Fed’s upper management lacks both gender and racial diversity. Among executives and mid-level managers at the Board of Governors, 43% are women and 34% are non-White. The nation as a whole is about 40% non-White.

The numbers are less diverse among the central bank’s ranks of economists, who most directly influence policy. Only about a quarter of the organisation’s 820 economists are women, and just above a quarter are minorities.

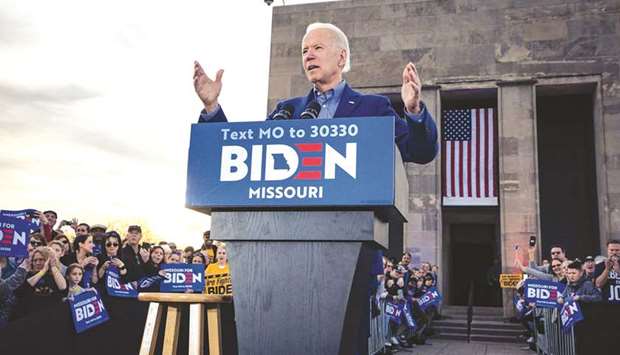

Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden speaks to the crowd during the Joe Biden Campaign Rally at the National World War I Museum and Memorial on March 7 in Kansas City, Missouri. Biden wants the Fed to u201caggressivelyu201d target inequality, even leaving open the possibility of asking Congress to create a third mandate for the central bank.