Japan’s ‘Abenomics’, which is a combination of aggressive monetary and fiscal expansion with structural reforms is expected to be continued into the post-Abe era, QNB has said in an economic commentary.

On August 28, Shinzo Abe announced his resignation as prime minister of Japan. The decision followed a deterioration of his health and the need for comprehensive medical treatment.

Effectively, this development marks the end of a political era, as Abe was the longest serving prime minister in Japan’s history (2012-2020).

“Make no mistake, the change of leadership in Japan is no small matter, especially as the country faces a plethora of challenges, including the Covid-19 pandemic, the current economic recession and the fast geopolitical movements in Asia. While the transition may open the debate for some policy changes, we believe that the basic macroeconomic tenets of the last few years should remain intact or could even be deepened,” QNB noted.

In other words, the economic doctrine often referred to as Abenomics is expected to be continued into the post-Abe era. QNB expects such a continuation for three reasons.

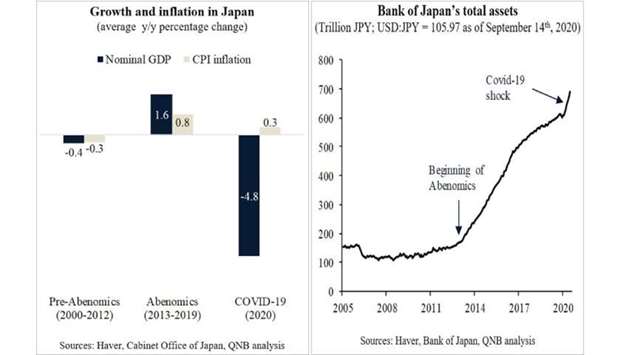

First, despite some progress thus far, Abenomics still did not fully deliver on its mandate to steer Japan completely away from the deflationary trap of low growth, low inflation and high levels of indebtedness. In order to achieve that, the country needs to produce more inflation and faster nominal GDP growth. While there was a significant improvement on both metrics vis-à-vis the previous period, they were still undershooting strategic targets. Ideally, for Japan, nominal growth and inflation should run above 2%.

Second, the massive Covid-19 shock amplifies Japan’s economic woes, as nominal GDP growth collapses, deflationary pressures build up and the level of indebtedness increases. Under such conditions, the policy measures under Abenomics will need to be used even more aggressively.

This includes more monetary easing and an even looser fiscal stance. A strong policy push will be necessary to jump start the economy again, preventing another negative deflationary spiral.

Third, given that Japan’s official rates have already reached the effective lower bound (rates are currently slightly negative by 10 basis points), policy alternatives are few and far between. The government needs to ramp up the fiscal impulse and this requires more coordination with the Bank of Japan (BoJ).

In fact, in order to respond to such needs, the BoJ will have to expand even more its balance sheet. As it stands now, the BoJ’s total assets amount to JPY 690tn ($6.5tn) or about 125% of the country’s GDP.

Despite the bloated size of the BoJ’s balance sheet, QNB said there is still theoretically more room for quantitative easing or large scale asset purchases.

The BoJ now owns about 54% of Japan’s outstanding government securities and holds the equivalent of 6% of the total market capitalisation of the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

“All in all, we believe that Abenomics will enter a second phase in post-Abe’s Japan. Monetary and fiscal authorities will likely continue to be bold, sizing up their unorthodox measures in response to the Covid-19 shock.

“Therefore, ‘Abenomics 2’ should provide important information for other policymakers as more advanced economies follow Japan in the use of ever expanding economic stimulus measures.

In a world of low growth and low inflation, Abenomics could well end up going global,” QNB said.

QNB graph