Nearly 15 years ago, then-Senator Joe Biden voted to fund hundreds of miles of new fencing along the border with Mexico.

He was joined by Senators Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama and other Democrats.

One of the first things President-elect Biden said he will do after being sworn in on January 20 is halt the construction of President Donald Trump’s border wall, though he doesn’t plan on tearing down what has been built so far.

About $15 billion has been spent on the project and 450 miles of wall have been constructed, all but 12 miles of it replacing some kind of existing barrier.

Biden has pledged to quickly undo many Trump policies, including some of the more disputed immigration measures enacted over the past four years.

He has vowed to reinstate the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals programme, end the travel ban from mostly majority-Muslim countries and African nations, and eventually raise the limit on refugees allowed into the United States.

Biden has proposed a task force charged with reuniting hundreds of undocumented immigrant children with their parents after being separated by federal authorities.

He also has promised to pursue a comprehensive overhaul of the immigration system with Congress within his first 100 days in office. That has been a goal of many Democrats and bipartisan coalitions for decades, but immigrant advocates question whether it can be achieved now — or even whether it should be, given the likely trade-offs.

As Biden’s own history shows, immigration policies, particularly regarding enforcement, don’t always neatly break down along party lines, even if it seemed that way in recent years with Democrats universally denouncing Trump’s more controversial moves and harsh rhetoric about undocumented immigrants.

Americans across the political spectrum, and leaders in both parties, want a solution for illegal immigration, control of the border and sensible, workable immigration laws. For decades, Washington mostly has struggled to do any of that, even in less-volatile times.

Biden’s border security plans call for increased screening at ports of entry, particularly for illegal drugs coming up through Mexico, along with more investment in surveillance technology. He also wants to work on economic and security measures with Mexico and Central American countries — ideas he backed when he voted for the Secure Border Fence Act of 2006.

While many Democrats applaud Biden’s approach, some say the United States has to be careful and not send a message that border enforcement is going away.

“We’ve got to make sure that we don’t give an impression that we have open borders,” Representative Henry Cuellar, D- Texas, told The Dallas Morning News. “The criminal organisations, they hire people, they know what our policies are. We don’t want them to go and advertise that there’s no wall so start coming into the US, and then we start seeing caravans again. It’s a balance.”

One of the more confounding aspects of Trump’s immigration policy regards the DACA programme. Partisans tended to be split over other programmes, such as building the wall and seeking to limit asylum.

But polls consistently showed DACA had broad support among Democrats, Republicans and independents. Leaders of both parties, including Trump at times, said they wanted to find a way to keep DACA recipients here. Yet the president took legal action early in his term to end the Obama administration programme, which gives temporary legal status to undocumented immigrants who were brought to the US as children.

That kept more than 600,000 DACA recipients in limbo, uncertain whether they would be deported to homelands many hardly know. The courts have blocked Trump, and those immigrants have a brighter future with a Biden administration poised to take control.

While the deportation threat appears to be evaporating, how Biden will make DACA permanent is unclear. In theory, doing it by executive order like President Obama did to create the programme leaves DACA open to legal challenges that maintain congressional action is necessary.

Given the backing DACA has, it would seem standalone legislation to codify the programme would have a good chance of passage, but that’s what many thought in the past and it didn’t happen.

Biden has vowed to pursue a comprehensive immigration bill that could include DACA and a pathway to citizenship for an estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants in the United States, among other things.

But natural supporters are not confident all-inclusive legislation would make it, with Democrats in control of the White House and the House of Representatives, and Republicans possibly still holding the Senate (depending on the outcome of two Georgia Senate elections in January).

For one thing, the administration has a lot of priorities, with addressing the deadly Covid-19 pandemic and its economic fallout being the first among them.

Also, even if Democrats win both seats in Georgia, Republicans in the Senate likely will still have enough leverage to be at the negotiating table on an immigration bill.

Immigrant advocates contend that means a continuation of GOP demands for more military-like border enforcement and crackdowns in the country’s interior.

“When activists hear comprehensive immigration reform, it’s like PTSD,” Cristina Jimenez, an immigrant leader and co-founder of United We Dream, told Newsweek. She was an informal adviser to the Biden campaign on immigration.

“It’s a package with harmful provisions for our community in exchange for a pathway to citizenship. It does not work for us and we need to break away from the old framework.”

The border wall will be halted and it looks like DACA recipients will get to stay. But a close presidential race, a smaller Democratic majority in the House and a Senate still up for grabs have led many analysts to conclude there was no sweeping mandate in this election.

That goes for the notion of what direction immigration legislation may take. — Tribune News Service

Michael Smolens is a columnist for The San Diego Union-Tribune.

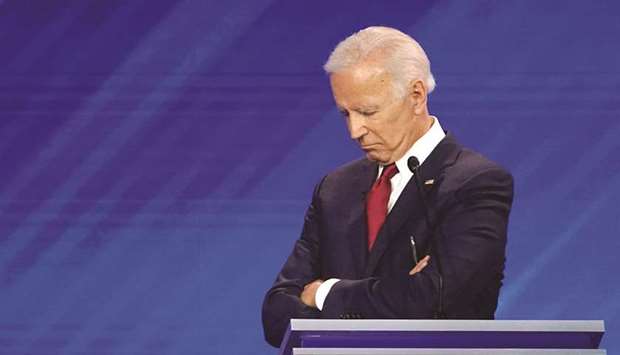

CAUTION: While many Democrats applaud President-elect Joe Biden’s approach, some say the United States has to be careful and not send a message that border enforcement is going away. (Reuters)