Before the pandemic, psychoanalyst Josh Cohen’s patients might come into his consulting room, lie down on the couch and talk about the traffic or the weather, or the rude person on the tube. Now they appear on his computer screen and tell him about brain fog. They talk with urgency of feeling unable to concentrate in meetings, to read, to follow intricately plotted television programmes. “There’s this sense of debilitation, of losing ordinary facility with everyday life; a forgetfulness and a kind of deskilling,” says Cohen, author of the self-help book How to Live. What to Do. Although restrictions are now easing across the UK, with greater freedom to circulate and socialise, he says lockdown for many of us has been “a contraction of life, and an almost parallel contraction of mental capacity”.

This dulled, useless state of mind – epitomised by the act of going into a room and then forgetting why we are there – is so boring, so lifeless. But researchers believe it is far more interesting than it feels: even that this common experience can be explained by cutting-edge neuroscience theories, and that studying it could further scientific understanding of the brain and how it changes. I ask Jon Simons, professor of cognitive neuroscience at the University of Cambridge, could it really be something “sciencey”? “Yes, it’s definitely something sciencey – and it’s helpful to understand that this feeling isn’t unusual or weird,” he says. “There isn’t something wrong with us. It’s a completely normal reaction to this quite traumatic experience we’ve collectively had over the last 12 months or so.”

What we call brain fog, Catherine Loveday, professor of cognitive neuroscience at the University of Westminster, calls poor “cognitive function”. That covers “everything from our memory, our attention and our ability to problem-solve to our capacity to be creative. Essentially, it’s thinking.” And recently, she’s heard a lot of complaints about it: “Because I’m a memory scientist, so many people are telling me their memory is really poor, and reporting this cognitive fog,” she says. She knows of only two studies exploring the phenomenon as it relates to lockdown (as opposed to what some people report as a symptom of Covid-19, or long Covid): one from Italy, in which participants subjectively reported these sorts of problems with attention, time perception and organisation; another in Scotland which objectively measured participants’ cognitive function across a range of tasks at particular times during the first lockdown and into the summer. Results showed that people performed worse when lockdown started, but improved as restrictions loosened, with those who continued shielding improving more slowly than those who went out more.

Loveday and Simons are not surprised. Given the isolation and stasis we have had to endure until very recently, these complaints are exactly what they expected – and they provide the opportunity to test their theories as to why such brain fog might come about. There is no one explanation, no single source, Simons says: “There are bound to be a lot of different factors that are coming together, interacting with each other, to cause these memory impairments, attentional deficits and other processing difficulties.”

One powerful factor could be the fact that everything is so samey. Loveday explains that the brain is stimulated by the new, the different, and this is known as the orienting response: “From the minute we’re born – in fact, from before we’re born – when there is a new stimulus, a baby will turn its head towards it. And if as adults we are watching a boring lecture and someone walks into the room, it will stir our brain back into action.”

Most of us are likely to feel that nobody new has walked into our room for quite some time, which might help to explain this sluggish feeling neurologically: “We have effectively evolved to stop paying attention when nothing changes, but to pay particular attention when things do change,” she says. Loveday suggests that if we can attend a work meeting by phone while walking in a park, we might find we are more awake and better able to concentrate, thanks to the changing scenery and the exercise; she is recording some lectures as podcasts, rather than videos, so students can walk while listening. She also suggests spending time in different rooms at home – or if you only have one room, try “changing what the room looks like. I’m not saying redecorate – but you could change the pictures on the walls or move things around for variety, even in the smallest space.”

The blending of one day into the next with no commute, no change of scene, no change of cast, could also have an important impact on the way the brain processes memories, Simons explains. Experiences under lockdown lack “distinctiveness” – a crucial factor in “pattern separation”. This process, which takes place in the hippocampus, at the centre of the brain, allows individual memories to be successfully encoded, ensuring there are few overlapping features, so we can distinguish one memory from another and retrieve them efficiently. The fuggy, confused sensation that many of us will recognise, of not being able to remember whether something happened last week or last month, may well be with us for a while, Simons says: “Our memories are going to be so difficult to differentiate. It’s highly likely that in a year or two, we’re still going to look back on some particular event from this last year and say, when on earth did that happen?”

Perhaps one of the most important features of this period for brain fog has been what Loveday calls the “degraded social interaction” we have endured. “It’s not the same as natural social interaction that we would have,” she says. “Our brains wake up in the presence of other people – being with others is stimulating.” We each have our own optimum level of stimulation – some might feel better able to function in lockdown with less socialising; others are left feeling dozy, deadened.

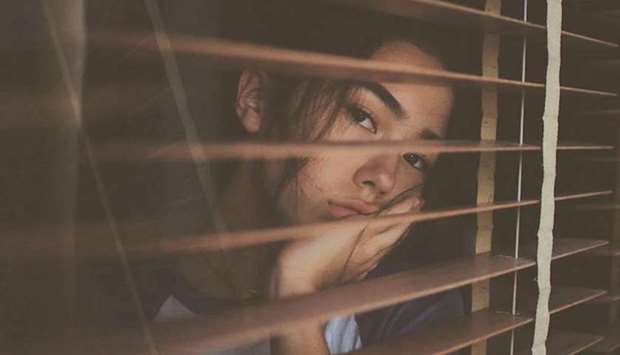

Woman in isolation.