Iraqis elect a new parliament tomorrow two years after a wave of anti-government protests swept the war-scarred country, but analysts say the vote is unlikely to deliver major change.

Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi’s political future hangs in the balance, with few observers willing to predict who will come out on top after the lengthy backroom haggling that usually follows Iraqi elections.

A new single-member constituency system for electing Iraq’s 329 lawmakers is supposed to boost independents versus the traditional blocs largely centred on religious, ethnic and clan affiliations.

The election is being held a year early in a rare concession to the youth-led protest movement that broke out in 2019 against a political class widely blamed for graft, unemployment and crumbling public services.

Hundreds died during the protests, and dozens more anti-government activists have been killed, kidnapped or intimidated in recent months, with accusations armed groups have been behind the violence.

Many activists have urged a boycott of the polls, and record low turnout is predicted among Iraq’s 25mn eligible voters, while experts predict the main parties are likely to maintain their grip on power. The vote is “unlikely to serve as an agent of change”, said Ramzy Mardini of the University of Chicago’s Pearson Institute.

“The election is meant to be a signal of reform, but ironically those advocating for reform are choosing to not participate...as a protest against the status quo.”

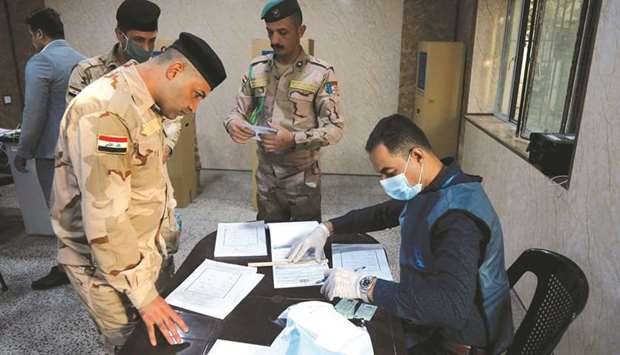

Security forces, displaced people and prisoners cast the first ballots in the election yesterday, two days before the rest of the country.

In Baghdad, there was a heavy security force presence outside polling stations.

Iraq is mired in corruption and economic crisis, and nearly a third of its people live in poverty despite the country’s oil wealth.

The risk of violence is rising amid a proliferation of armed factions and a militant resurgence, even as the country tries to emerge from almost two decades of conflict.

A dozen Western governments including the US and the UK on Wednesday called on “all parties to respect the rule of law and the integrity of the electoral process”. The United Nations and the European Union have deployed vote monitors and observers. Iraq’s political scene remains deeply polarised over sensitive issues including the presence of US troops and the influence of a neighbouring nation. But even in the fragmented parliament, where alliances are stitched up and then undone, political blocs will have to overcome their differences when it’s time to name a prime minister.

The pick for PM will “depend on the level of representation of the different blocs,” said Iraqi political scientist Ali al-Baidar.

He noted the ambitions of the Sadrist bloc, headed by firebrand populist cleric Moqtada Sadr, the former leader of an anti-US militia.

Sadr is considered a favourite in the polls, and would like a free hand to name the prime minister.

But the Hashed al-Shaabi, or Popular Mobilisation Forces, also wants to hold onto its gains.

The powerful network of former paramilitary groups helped defeat the Islamic State group in 2017.

Any compromise candidate for prime minister will have to have the tacit blessing of Tehran and Washington, that are both Baghdad allies. When it comes to forming a government, parties will likely face initial internal disagreement, according to Mardini, “but that’s a bargaining tactic”.

“The core of government formation will remain the established political parties and bosses.

Independents can only be a superficial accessory to it.”

Baidar left open the possibility that incumbent Kadhimi would hang onto his position.

In a televised speech yesterday evening, Kadhimi adopted a reformist tone. He said Iraqis had a “historic opportunity” to elect “competent individuals...who are not tarnished by corruption” and are capable of launching “comprehensive reform at every level”. Far from the political horse-trading, many Iraqis feel deeply disillusioned by a political establishment that they blame for the country’s ills.

Jawad, an elderly man who declined to provide his surname, whose son died two years ago when authorities used force to put down the anti-government protests.

He said he was still waiting for justice and wouldn’t vote tomorrow, charging that “my son was killed by the same militias that make up the corrupt government”.

Members of Iraqi Security forces get ready to cast their vote two days ahead of Iraq’s parliamentary elections in a special process, in Mosul, yesterday.