*Abdulrazak Gurnah wins the 2021 Nobel prize for literature

*First black African writer in 35 years to win prestigious award

*The theme of the refugee’s disruption runs throughout his work

Abdulrazak Gurnah, who won this year's Nobel prize in literature, was awarded for his “uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents”, the Nobel committee has said.

Gurnah grew up on one of the islands of Zanzibar before fleeing persecution of Arabs and arriving in England as a student in the 1960s. He has published 10 novels as well as a number of short stories.

Anders Olsson, chair of the Nobel committee, said that Gurnah’s novels – from his debut Memory of Departure, about a failed uprising, to his most recent, Afterlives – “recoil from stereotypical descriptions and open our gaze to a culturally diversified East Africa unfamiliar to many in other parts of the world”.

No black African writer has won the prize since Wole Soyinka in 1986. Gurnah is the first black writer to win since Toni Morrison in 1993.

“[Gurnah] has consistently and with great compassion penetrated the effects of colonialism in East Africa, and its effects on the lives of uprooted and migrating individuals,” Olsson told journalists in Stockholm.

His longtime editor, Alexandra Pringle at Bloomsbury, said Gurnah’s win was “most deserved” for a writer who has not previously received due recognition.

“He is one of the greatest living African writers, and no one has ever taken any notice of him and it’s just killed me. I did a podcast last week and in it I said that he was one of the people that has been just ignored. And now this has happened,” she said.

Pringle said Gurnah had always written about displacement, “but in the most beautiful and haunting ways of what it is that uproots people and blows them across continents”.

"In Gurnah’s literary universe, everything is shifting – memories, names, identities. This is probably because his project cannot reach completion in any definitive sense,” said Olsson. “An unending exploration driven by intellectual passion is present in all his books, and equally prominent now, in Afterlives, as when he began writing as a 21-year-old refugee.”

Gurnah was born in 1948, growing up in Zanzibar. When Zanzibar went through a revolution in 1964, citizens of Arab origin were persecuted, and Gurnah was forced to flee the country when he was 18. He began to write as a 21-year-old refugee in England, choosing to write in English, although Swahili is his first language. His first novel, Memory of Departure, was published in 1987. He has until recently been professor of English and postcolonial literatures at the University of Kent, until his retirement.

Gurnah’s Nobel Prize win sparked both joy and debate over identity in Tanzania..

Many in the country acknowledge the recognition of Gurnah’s work among the handful of African novelists to have won the prestigious prize, but others question whether Tanzanians can truly claim the England-based writer as their own.

Both the presidents of Tanzania and semi-autonomous Zanzibar were swift in hailing Gurnah’s achievement.

“The prize is an honor to you, our Tanzanian nation and Africa in general,” Tanzanian President Samia Suluhu Hassan tweeted. For his part, Zanzibar leader Hussein Ali Mwinyi said, “We fondly recognise your writings that are centred on discourses related to colonialism. Such landmarks, bring honour not only to us but to all humankind.”

Meanwhile Gurnah, in an interview with AFP news agency, stressed his close ties to Tanzania.

“Yes, my family is still alive, my family still lives there,” the retired University of Kent professor said. “I go there when I can. I’m still connected there … I am from there. In my mind I live there.”

Dual-citizenship has been a long-debated issue, with more and more Tanzanians – especially those in the diaspora – advocating for its implementation. Successive governments have steered clear of it, often citing constitutional restrictions.

“One of the reasons Tanzania can’t allow dual citizenship is the fear that Abdulrazak Gurnah & his grandparents, who fled Zanzibar to escape the persecution of Arabs during the Zanzibar Revolution, would return and claim their stolen assets. And we’re shamelessly celebrating his victory?” Erick Kabendera, a journalist, wrote.

But others believe his long time spent abroad should not deprive him of his roots.

“Gurnah identifies himself as Tanzanian of Zanzibar origin. Living in diaspora, having been exiled or even feeling dislocated from his country does not take away his heritage and identity. That is part of who he is,” said Ida Hadjivayanis, lecturer of Swahili studies at School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

A Zanzibari native herself, Hadjivayanis said she was thrilled beyond words about Gurnah’s win.

“Gurnah is an author who speaks the truth,” she said, describing his work as honest. “Their (characters in the books) experiences are familiar, their link to home (Tanzania and especially Zanzibar) often hits a chord.”

Gurnah grew up on one of the islands of Zanzibar before fleeing persecution of Arabs and arriving in England as a student in the 1960s. He has published 10 novels as well as a number of short stories.

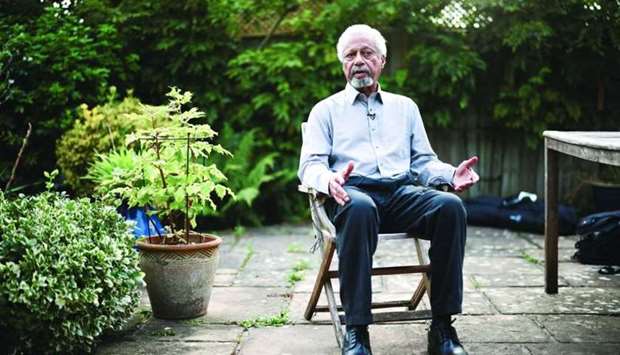

Tanzanian novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah, winner of the 2021 Nobel Prize for Literature, poses at his home in Canterbury, Britain, October 7, 2021. REUTERS/Henry Nicholls

Anders Olsson, chair of the Nobel committee, said that Gurnah’s novels – from his debut Memory of Departure, about a failed uprising, to his most recent, Afterlives – “recoil from stereotypical descriptions and open our gaze to a culturally diversified East Africa unfamiliar to many in other parts of the world”.

No black African writer has won the prize since Wole Soyinka in 1986. Gurnah is the first black writer to win since Toni Morrison in 1993.

“[Gurnah] has consistently and with great compassion penetrated the effects of colonialism in East Africa, and its effects on the lives of uprooted and migrating individuals,” Olsson told journalists in Stockholm.

His longtime editor, Alexandra Pringle at Bloomsbury, said Gurnah’s win was “most deserved” for a writer who has not previously received due recognition.

“He is one of the greatest living African writers, and no one has ever taken any notice of him and it’s just killed me. I did a podcast last week and in it I said that he was one of the people that has been just ignored. And now this has happened,” she said.

Pringle said Gurnah had always written about displacement, “but in the most beautiful and haunting ways of what it is that uproots people and blows them across continents”.

"In Gurnah’s literary universe, everything is shifting – memories, names, identities. This is probably because his project cannot reach completion in any definitive sense,” said Olsson. “An unending exploration driven by intellectual passion is present in all his books, and equally prominent now, in Afterlives, as when he began writing as a 21-year-old refugee.”

Gurnah was born in 1948, growing up in Zanzibar. When Zanzibar went through a revolution in 1964, citizens of Arab origin were persecuted, and Gurnah was forced to flee the country when he was 18. He began to write as a 21-year-old refugee in England, choosing to write in English, although Swahili is his first language. His first novel, Memory of Departure, was published in 1987. He has until recently been professor of English and postcolonial literatures at the University of Kent, until his retirement.

Gurnah’s Nobel Prize win sparked both joy and debate over identity in Tanzania..

Many in the country acknowledge the recognition of Gurnah’s work among the handful of African novelists to have won the prestigious prize, but others question whether Tanzanians can truly claim the England-based writer as their own.

Both the presidents of Tanzania and semi-autonomous Zanzibar were swift in hailing Gurnah’s achievement.

“The prize is an honor to you, our Tanzanian nation and Africa in general,” Tanzanian President Samia Suluhu Hassan tweeted. For his part, Zanzibar leader Hussein Ali Mwinyi said, “We fondly recognise your writings that are centred on discourses related to colonialism. Such landmarks, bring honour not only to us but to all humankind.”

Meanwhile Gurnah, in an interview with AFP news agency, stressed his close ties to Tanzania.

“Yes, my family is still alive, my family still lives there,” the retired University of Kent professor said. “I go there when I can. I’m still connected there … I am from there. In my mind I live there.”

Dual-citizenship has been a long-debated issue, with more and more Tanzanians – especially those in the diaspora – advocating for its implementation. Successive governments have steered clear of it, often citing constitutional restrictions.

“One of the reasons Tanzania can’t allow dual citizenship is the fear that Abdulrazak Gurnah & his grandparents, who fled Zanzibar to escape the persecution of Arabs during the Zanzibar Revolution, would return and claim their stolen assets. And we’re shamelessly celebrating his victory?” Erick Kabendera, a journalist, wrote.

But others believe his long time spent abroad should not deprive him of his roots.

“Gurnah identifies himself as Tanzanian of Zanzibar origin. Living in diaspora, having been exiled or even feeling dislocated from his country does not take away his heritage and identity. That is part of who he is,” said Ida Hadjivayanis, lecturer of Swahili studies at School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

A Zanzibari native herself, Hadjivayanis said she was thrilled beyond words about Gurnah’s win.

“Gurnah is an author who speaks the truth,” she said, describing his work as honest. “Their (characters in the books) experiences are familiar, their link to home (Tanzania and especially Zanzibar) often hits a chord.”