Former Mexican President Luis Echeverria, who took office in 1970 promising a democratic opening for the country but oversaw six of the harshest years of a so-called "dirty war" against dissidents, has died aged 100.

Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador on Twitter confirmed the death on Saturday, expressing his condolences to Echeverria's family.

As an elderly man, Echeverria escaped attempts by Mexican prosecutors to indict him for genocide for his role in two infamous massacres of student protesters in 1968 and 1971 that helped define an era of heavy-handed state repression.

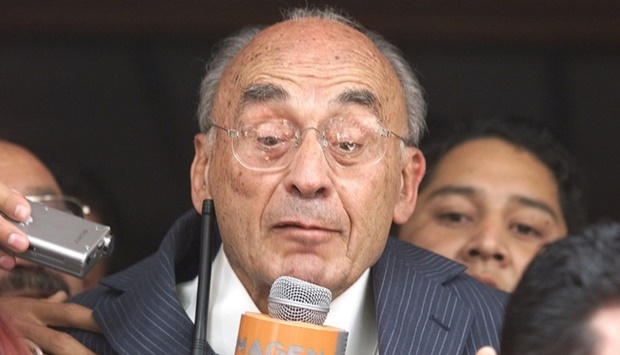

Bald and bespectacled, Echeverria denied wrongdoing and said his conscience was clear. He refused to testify about crimes that have not been fully cleared up to this day.

A loyal son of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, which ruled Mexico for 71 years until its ousting in a 2000 election, Echeverria believed in preserving the all-encompassing party system that reached into every sphere of public life.

His 1970-1976 presidency was tainted from the outset by accusations that he ordered troops to open fire on thousands of peacefully demonstrating students in the Mexico City area of Tlatelolco on Oct. 2, 1968 while serving as interior minister.

At the time, the government said just 30 people had been killed and injured in the massacre, carried out days before the Olympic Games opened in Mexico City. Some witnesses said many more bodies were carted off from the scene.

Hundreds of students were beaten and jailed after the protest, which occurred when student uprisings were erupting worldwide. A definitive death toll has never been given.

As interior minister, Echeverria led a group of top officials crafting a response to the student uprisings, according to declassified US government documents.

Keen to wipe the slate clean during his presidency, Echeverria promised a "democratic opening". He released people imprisoned after the massacre and courted the intellectual left, promoting them to prominent positions in government.

But from the late 1960s to early 1980s, activists say PRI security forces were responsible for a brutal campaign against leftist intellectuals and critical journalists, many of whom were killed and disappeared during Echeverria's rule.

On June 10, 1971, the day of the Corpus Christi Catholic celebration, a paramilitary force known as Los Halcones, or The Falcons, attacked a student protest with pistols, rifles, tear gas and batons, killing or wounding dozens of demonstrators.

Born on Jan. 17, 1922 to a middle class family in Mexico City, Echeverria was know for embracing a leftist foreign policy while cozying up to Washington.

U.S. President Richard Nixon was fond of Echeverria.

"He's strong, he wants to play the right games," Nixon said of Echeverria in a recorded conversation with the director of the Central Intelligence Agency.

During his presidency, Echeverria had plans to redistribute lands of the wealthy to peasants and espoused a protectionist economic policy of high tariffs, state intervention and preference for domestic products.

As the public sector ballooned and government borrowing soared, Echeverria alienated the business class, which stopped investing and sent its capital out of the country.

Mexico's foreign debt sextupled and the peso's value almost halved during Echeverria's term in office, leading to a currency devaluation shortly before his term expired.

In 2006, a judge ordered Echeverria to be placed under house arrest for his connection to the student killings.

But in March 2009, a court ruled the army crackdown did not qualify as genocide, and upheld prior rulings that a 30-year statute of limitations for the crimes had expired.

In 2020, after some 10 years out of the public eye, Mexican media photographed Echeverria waiting in a wheelchair to receive a Covid-19 vaccine, wearing a wide-brimmed straw hat and rolling up the sleeve of a lilac-colored shirt for the shot.

International / US/Latin America

Former Mexican President Echeverria, famed for role in repression, dies at 100

Luis Echeverria makes a statement in Mexico City July 9, 2002. Reuters