Fifty years ago, the Cold War was transposed to a chessboard as Bobby Fischer of the United States took on defending world champion Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union in a thrilling East-West clash dubbed the “match of the century”.

Some 50mn TV viewers tuned into the two-month-long tussle in the Icelandic capital Reykjavik, where chess’s enfant terrible Fischer set out to wrest the championship from the Soviet Union, which had dominated the game for decades.

AFP reported daily from the competition. This account is based on its reporting.

Polar opposites

On one side of the table is Fischer, an eccentric, fiercely competitive 29-year-old former boy wonder, who was holding his own among America’s greats by the age of 12 and has already won eight US chess championships.

Born in Chicago, Fischer grew up in the New York suburb of Brooklyn where his older sister taught him chess at the age of six.

He became the world’s youngest ever chess grand master at the age of 15 and dropped out of school to focus on the game.

AFP’s correspondent in Reykjavik says “he has few friends and doesn’t care to make any” and that his motto is: “It’s not enough to defeat an adversary, you have to crush them.”

He goes into the competition having won 101 out of his previous 120 games.

In the other seat is 35-year-old Boris Spassky, a trained journalist and married father of two children who has been world champion for three years.

Born in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) in 1937 he was sent to an orphanage in Siberia during the Nazi German siege of the city during World War II.

A pure product of the Soviet chess machine, he began playing at five and became world champion at 19.

A likeable, modest character, he is the antithesis of the cantankerous Fischer.

Temper tantrums

Fischer is the first US-born player to have a stab at the title (since 1946, the two finalists have always been Soviet).

Neutral countries vie to host the match, which is eventually awarded to Iceland.

Fischer makes a series of demands before agreeing to participate. The venue, a sports hall, must be sound-proofed, fitted with a new carpet and the room temperature kept to 22.5C.

But on the eve of the competition, he has still not shown up and Spassky is growing impatient.

Henry Kissinger, who is US national security advisor at the time under President Richard Nixon, calls Fischer and convinces him to take part.

AFP reports that the US champion “appears tired” when he lands in Reykjavik on July 4. He ducks out of the opening ceremony. An outraged Spassky demands an apology.

The competition finally gets underway on July 11, nine days late.

‘Scandal of the century’

Spassky arrives 20 minutes early to the opening game to “vigorous applause” from the 2,500 spectators in the packed hall. Fischer dashes in at the last minute, “pushes past the photographers, rushes towards Spassky, shakes his hand” and sits down. The game is finally on.

The two proceed cautiously and at the 28th move, the game looks headed for a draw. But Fischer then makes two bad moves and resigns on the 56th move.

Stung by his loss, he demands that all cameras be removed from the hall. When the request is denied, he refuses to show up to the second game, forfeiting it.

“The spectators are disappointed and exasperated,” AFP reports.

Icelandic daily Timinn declares that the match of the century has turned into the “scandal of the century”.

As the third game looms Fischer is nowhere to be found. Kissinger again picks up the phone. “Please, continue the game,” Fischer later quotes him as pleading.

The hall is packed when the competition resumes on July 16, but the stage is empty. Spassky has accepted Fischer’s demand that they play in a small back room normally used for ping pong (with a camera in the ceiling broadcasting the events to the main hall outside).

Some commentators see Spassky’s concession as a bad omen for the Russian, who goes on to lose the game.

The fourth is a draw and Spassky resigns the fifth.

The two are now neck-and-neck.

Games for the history books

The 6th game is one of the toughest of the competition. Spassky throws in the towel at the 41st move.

“I’m proud of this game, it was one of my best,” Fischer tells AFP, adding: “When Spassky joined the crowd in applauding my victory I thought ‘what a gentleman’.”

Spassky also resigns the 13th game, a chess masterclass, according to AFP’s correspondent, who reported that, after congratulating his opponent, Spassky “sits back down in contemplation for six minutes, his gaze lost in the chessboard”.

Fischer is looking increasingly assured of victory. “He will be champion,” his sister Joan tells AFP after the seventh game.

The Russian asks that the 14th game be postponed and the next seven are all draws.

Game 21, which goes to Fischer, turns out to be the last. The next day Spassky resigns the game, making Fischer, who is still asleep, the 11th world chess champion, with a final score of 12.5-8.5.

From hero to zero

With the chessboard seen as a metaphor for great power politics, Fischer’s win is feted in the United States as a symbolic victory of capitalism over communism.

Nixon invites Fischer to the White House

A broken Spassky returns to an icy reception in the Soviet Union, where he is banned from taking part in chess competitions and placed under surveillance by the KGB, the secret police.

In 1976, he marries a Frenchwoman and moves to Paris, but the self-professed Russian nationalist later returns to Moscow.

Fischer never plays another chess competition.

In 1975, he refuses to defend his title against the Soviet Union’s Anatoly Karpov and therefore loses it. A conspiracy theorist with a visceral hatred of “world Jewry” he disappears for years at a time, re-emerging in 1992 for a rematch against Spassky in Yugoslavia, despite the war-torn country being under US sanctions.

In 2004 he renounces his US citizenship and later moves to Iceland where he dies on January 17, 2008 at the age of 64 — the number of squares on a chessboard.

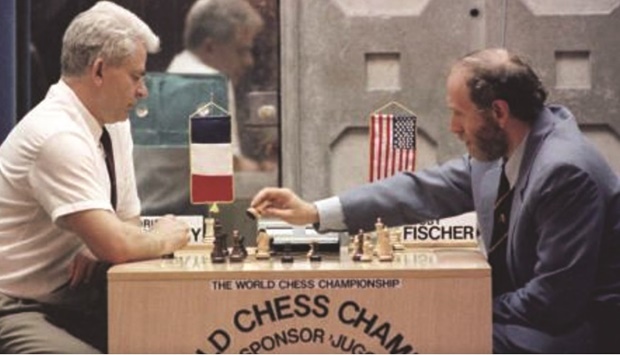

Former world chess champion Bobby Fischer (right) moves a piece during a September 1992 match against his archrival, the Soviet Union’s Boris Spassky, in the Yugoslav resort of Sveti Stefan in this September 3, 1992 file photo. (Reuters)